Editor's Note: SHRM has partnered with Harvard Business Review to bring you relevant articles on key HR topics and strategies.

From Uber to Nike to CBS, recent exposés have revealed seemingly dysfunctional workplaces rife with misconduct, bullying and sexual harassment. For example, Susan Fowler's 2017 blog about Uber detailed not only her recollections of being repeatedly harassed, but what she described as a "game-of-thrones" environment, in which managers sought to one-up and sabotage colleagues to get ahead. A New York Times investigation described Uber as a "Hobbesian environment … in which workers are pitted against one another and where a blind eye is turned to infractions from top performers."

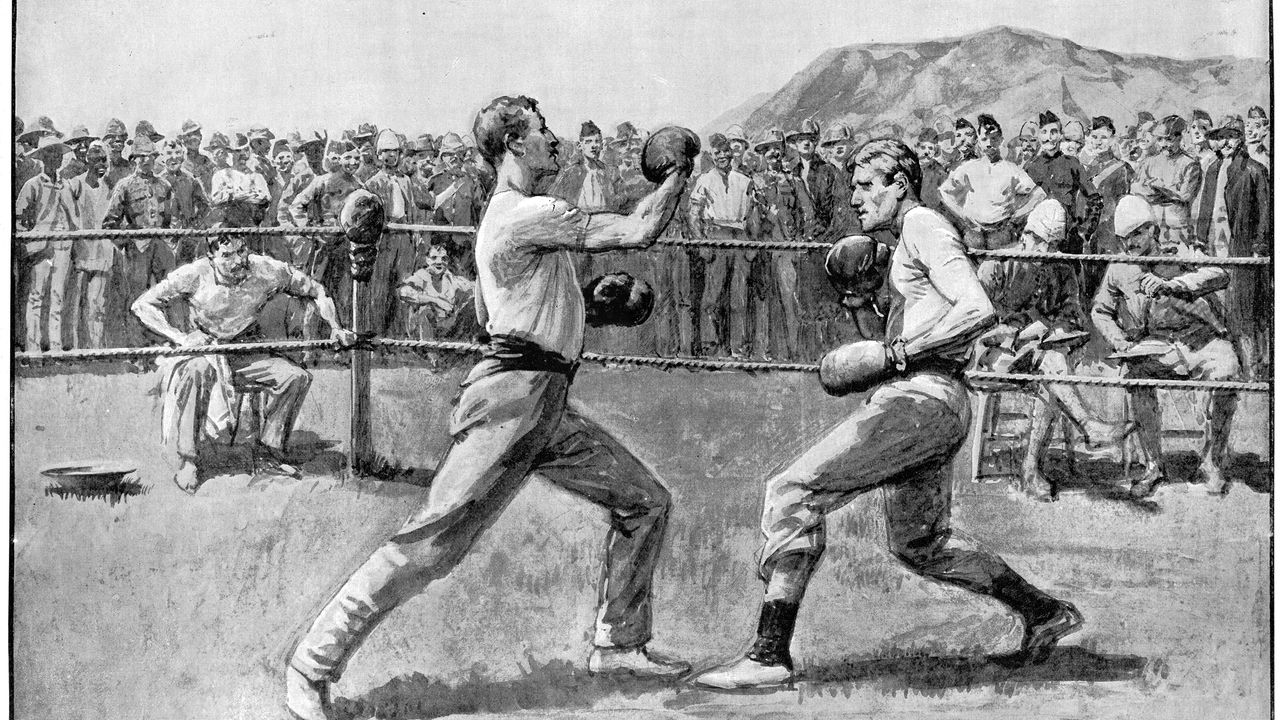

Why do companies get caught up in illegal behavior, harassment and toxic leadership? Our research identifies an underlying cause: what we call a "masculinity contest culture." This kind of culture endorses winner-take-all competition, where winners demonstrate stereotypically masculine traits such as emotional toughness, physical stamina and ruthlessness. It produces organizational dysfunction, as employees become hyper competitive to win.

Masculinity Contest Cultures

We surveyed thousands of workers in the U.S. and Canada from different organizations. Respondents rated whether various masculine qualities were highly prized in their workplace; they also reported on other organizational characteristics and their personal outcomes. Four masculine norms, which together define masculinity contest culture, emerged as highly correlated with each other and with organizational dysfunction:

- "Show no weakness": a workplace that demands swaggering confidence, never admitting doubt or mistakes, and suppressing any tender or vulnerable emotions ("no sissy stuff").

- "Strength and stamina": a workplace that prizes strong or athletic people (even in white collar work) or those who show off their endurance (e.g., by working extreme hours).

- "Put work first": a workplace where nothing outside the organization (e.g., family) can interfere with work, where taking a break or a leave represents an impermissible lack of commitment.

- "Dog eat dog": a workplace filled with ruthless competition, where "winners" (the most masculine) focus on defeating "losers" (the less masculine), and no one is trusted.

These norms take root in organizations because behaving in accordance with them is what makes someone a "man." As phrases like "man up" illustrate, being a man is something men must prove — not just once, but repeatedly. In many cultures around the world, someone becomes a "man" by behaving in ways that conform with cultural beliefs about what men are like — dominant, tough, risk taking, aggressive, rule breaking.

And it doesn't take much to make men feel like "less of a man." Men react defensively when they even just think about job loss, or receive feedback suggesting they have a "feminine" personality.

What all of this means is that masculinity is precarious: hard won, and easily lost. And the need to repeatedly prove manhood can lead men to behave aggressively, take unwarranted risks, work extreme hours, engage in cut-throat competition and sexually harass women (or other men), especially when they feel a masculinity threat.

At work, this pressure to prove "I have what it takes" shifts the focus from accomplishing the organization's mission to proving one's masculinity. The result: endless "mine's bigger than yours" contests, such as taking on and bragging about heavy workloads or long hours, cutting corners to out-earn others, and taking unreasonable risks either physically (in blue-collar jobs) or in decision-making (e.g., rogue traders in finance). The competition breeds unspoken anxiety (because admitting anxiety is seen as weak) and defensiveness (e.g., blaming subordinates for any failure), undermining cooperation, psychological safety, trust in coworkers, and the ability to admit uncertainty or mistakes. Together this creates miserable, counterproductive work environments that increase stress, burnout and turnover.

Masculinity contests are most prevalent — and vicious — in male-dominated occupations where extreme and precarious resources are at stake (fame, power, wealth, safety). Think about finance and tech startups, where billions of dollars are quickly made or lost; surgery, where high-stakes operations leave no room for error; and military and police units, where risky jobs are performed under strict chains of command.

Where does this leave women? Like everyone else, women must try to play the game to survive, and the few who succeed may do so by behaving just as badly as the men vying to win. But the game is rigged against women and minorities: Suspected of not "having what it takes," they must work harder to prove themselves while facing backlash for displaying dominant behaviors like anger and self-promotion. Women and minorities thus face a double-bind that makes them less likely to succeed; they may find it easier to survive by playing supporting roles to men who are winning the contest.

The Business Case Against Masculinity Contests

Organizations rely on cooperative teamwork to succeed. But masculinity contests lead people to focus on burnishing their personal image and status at the expense of others, even their organizations. Our research documents numerous negative consequences that harm the bottom line and put the organization's effectiveness and reputation at risk. Organizations that score high on masculinity contest culture tend to have toxic leaders who abuse and bully others to protect their own egos; low psychological safety such that employees do not feel accepted or respected, feeling unsafe to express themselves, take risks, or share new ideas; low work/family support among leaders, discouraging work-life balance; sexist climates where women experience either hostility or patronizing behavior; harassment and bullying, including sexual harassment, racial harassment, social humiliation and physical intimidation; higher rates of burnout and turnover; and higher rates of illness and depression among both male and female employees.

These problems create both direct costs (through turnover and harassment lawsuits) and indirect costs (through decreased innovation due to low psychological safety). Put simply, masculinity contest cultures are toxic to organizations and the men and women within them. In extreme cases, such as Uber, the pressure cooker explodes, severely damaging or even destroying the organization.

Changing Masculinity Contest Cultures

Despite being toxic, masculinity contest cultures persist for two reasons: (1) the association between toxic masculinity and success is so strong that people feel compelled to keep playing the game, despite the dysfunctional behavior it produces, and (2) questioning the masculinity contest marks one as a "loser," which disincentivizes people from pushing back. Dropping a diversity initiative onto these types of workplaces is unlikely to create meaningful change. In fact, current interventions, like those to prevent sexual harassment, typically fail or even backfire in these environments (by creating more harassment). Real change requires shutting down this game.

To accomplish this, organizations need to perform deeper, more committed work to examine and diagnose their cultures. These efforts must be led by those who have the power to spark serious reform. It is crucial to generate awareness of the masculinity contest and its role in creating organizational problems. For instance, people tend to attribute sexual harassment to a "few bad apples," ignoring how an organization's culture unleashed, allowed, and may have even rewarded the misconduct. When organizations do not tolerate bullying and harassment, the bad apples are kept in check and good apples do not go bad.

Two specific actions are a good place to start:

Establish a stronger focus on the organization's mission. Current trainings backfire, in part, because they focus on compliance and "what not to do," are often framed as trying to "make things better for the women and minorities" rather than for everyone, and seem unconnected to the organization's core mission. Effective interventions require authentic and meaningful connections to core organizational values and goals.

For example, researchers have documented how an energy company undermined masculinity contest norms on oil rigs through a safety intervention. The bottom line demanded reform: oil rig disasters cost lives and money, environmental destruction, legal liability and severe reputational damage. Leaders convinced workers that increased safety was central to the mission; and they monitored and rewarded desired behavior change. Workers were rewarded for voicing doubts or uncertainties about a procedure (rather than "showing no weakness"), for listening to each other (rather than obeying the "strongest" alpha male), for valuing safety and taking breaks (rather than "putting work first"), and for cooperating with and caring for coworkers (rather than "dog eat dog" competition). The need to prove manhood proved incompatible with the new mission-based rules. Not only were accidents and injuries reduced, but so was bullying, harassment, burnout and stress.

Organizations can leverage other core goals to motivate reform. Given the inherent dysfunctionality masculinity contest cultures create, chances are that almost any mission-related reform can help. For example, research demonstrates a common characteristic among innovative teams: psychological safety. Team members know that they can raise questions or voice doubts without eliciting ridicule or rejection. An initiative to foster innovation via greater psychological safety would naturally dampen the masculinity contest. As a by-product, the work environment should become more hospitable and inclusive toward women and minorities; after all, whose ideas are most often summarily ignored or dismissed in masculinity contest cultures?

Dispel misconceptions that "everyone endorses this." People fail to question masculinity contest norms lest they be tagged as a whiny, soft loser. As a result, everyone goes along to get along, publicly reinforcing norms they privately hate — people stay late just to be seen as putting work first, or laugh at a joke they actually think is offensive. Because people publicly uphold the norms, it appears as though everyone endorses them. Research has shown that people in masculinity contest cultures think their coworkers embrace these norms when in fact they do not, breeding pervasive but silent dissatisfaction alongside active complicity as people stay quiet to prove they belong.

Leaders can remedy this misperception by publicly rejecting masculinity contest norms and empowering others to voice their previously secret dissent. But they also need to walk the talk by changing reward systems, modeling new behavior, and punishing the misconduct previously overlooked or rewarded. Leaders also need to ensure that people who speak up are no longer punished or retaliated against for doing so, either formally (e.g., with job consequences) or informally (e.g., by reputation and ostracism).

When masculinity contest cultures become "the way business gets done," both organizations and the people within them suffer. Your organization may have a masculinity contest culture if, for example, expressing doubt is forbidden, "jocks" are preferred even though athleticism is irrelevant to job tasks, extreme hours are viewed as a badge of honor, or coworkers are treated as competitors rather than colleagues. Solving the problem requires meaningful commitment to culture change — to creating a work environment in which mission takes precedence over masculinity.

Jennifer L. Berdahl, PhD, is the professor of Leadership: Gender and Diversity at the University of British Columbia's Sauder School of Business. Her research focuses on sexual harassment and organizational cultures that encourage it. Peter Glick, PhD, is the Henry Merritt Wriston Professor at Lawrence University and a Senior Scientist with the Neuroleadership Institute. He specializes in talks about how organizations can overcome barriers to women's leadership and create a more optimal organizational culture. Marianne Cooper, PhD, is a sociologist at the VMware Women's Leadership Innovation Lab at Stanford University. She is an author of the Women in the Workplace reports by LeanIn.org and McKinsey & Company.

This article is reprinted from Harvard Business Review with permission. ©2018. All rights reserved.

Advertisement

An organization run by AI is not a futuristic concept. Such technology is already a part of many workplaces and will continue to shape the labor market and HR. Here's how employers and employees can successfully manage generative AI and other AI-powered systems.

Advertisement