Navigating Religious Inclusion at Work

As cultural change and new legal precedents are increasingly bringing religion to the forefront in the workplace, employers are left wondering how—and whether—they can draw a line between employees’ work and religious practice.

Dr. Mark Poznansky founded a Jewish employee resource group (ERG) at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston in 2022 after a website published a detailed map online that threatened him, his research and his affiliated hospital—along with various Jewish institutions. “It made me think we needed an organized Jewish community within our hospital system that could address the growing antisemitism in our society,” says Poznansky, the director of Mass General’s Vaccine and Immunotherapy Center and a professor at Harvard Medical School.

The group’s early days were spent lobbying for kosher food in the kitchen and organizing celebrations for Jewish holidays. When the Israel-Hamas war broke out in October, Poznansky says the group took on a new importance, and it began holding weekly support sessions for Jewish employees and those who identify with them so they could share what they were feeling about the war. “There’s a good proportion of Jewish people who have some family and friends in the country, and so it’s personal,” he says.

The Israel-Hamas war has intensified the spotlight on how religion can impact the workplace. Muslim employees at multiple workplaces have said they’ve been fired or had job offers rescinded after expressing their opinions about the conflict on social media. In one case, a Muslim esthetician in the Midwest said she was fired from her job because her employer alleged that her pro-Palestinian posts on social media supported “terrorism”—and that some of her clients felt unsafe around her. The woman said she was let go due to her faith, and that she was never given any proof that any of her clients felt uncomfortable with her.

Not surprisingly, advocacy groups for Jewish and Muslim communities have reported an increase in instances of antisemitism and Islamophobia in workplaces across the U.S. since the war began. Interfaith America, a group that provides consultation, training, curricula and resources to help institutions foster greater religious inclusivity, says more employers are expressing interest in its services.

The implications of expressing various viewpoints on the Israel-Hamas conflict in the workplace illustrate just how difficult it is for employers to adequately address issues connected to religion. Company leaders who opt to make statements about current events, especially those with a religious backdrop, should be sensitive to employees of all beliefs. It can be a difficult tightrope to walk: After the Hamas invasion of Israel and Israel’s subsequent bombing campaign in Gaza, a group of Palestinians, other Arabs, Muslims and some Jewish employees at Google wrote an open letter alleging that members of the company’s leadership were allowing racist language against Palestinians on internal communication channels and that managers were trying to fire those who expressed sympathy for the people of Gaza.

Religion in the Courts

Now that many employers encourage employees to bring their “whole selves” to work in the name of well-being, conversations about race, gender, sexual orientation, disability and, increasingly, religion have become more common. Not long before the Israel-Hamas war, two seminal Supreme Court rulings regarding religion in the workplace already had employers rethinking how they should address potentially difficult religious discussions in the office.

Historically, religious discrimination cases have been relatively rare, accounting for only between 3 percent and 4 percent of the charges brought by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). That changed during the COVID-19 pandemic as workers sought religious exemptions from employer vaccine mandates. In the fiscal year ending Sept. 30, 2022, religious discrimination accounted for almost 19 percent of charges brought by the EEOC .

The Supreme Court rulings regarding religion in the workplace have helped push the issue further into the spotlight. The first one, issued on June 29, involved Gerald Groff, a postal worker and evangelical Christian who observed the Sabbath on Sundays, meaning he didn’t work on that day. That became an issue when Groff’s local post office started delivering packages for Amazon on Sundays. Groff faced progressive discipline when he failed to show up for work on those days. He eventually quit and sued the U.S. Postal Service.

We’re entering a whole new world of religion in the workplace. It’s a whole new landscape.” —Frank Shuster

Groff’s case ultimately reached the Supreme Court. In Groff v. DeJoy, the court ruled unanimously in favor of Groff, finding that employers can only deny an employee’s request for religious accommodation if the organization can prove that granting it would result in a substantial hardship to the employer. The previous legal standard obligated employers to grant requests only if the cost to the organization was minimal.

One day after publishing its decision in the Groff case, the Supreme Court ruled similarly in 303 Creative LLC v. Elenis. The 6-3 decision was in favor of website designer Lorie Smith, a Christian who wanted the right to refuse to make wedding websites for same-sex couples due to her religious beliefs about marriage. The court ruled that the designer’s free speech rights trumped the state of Colorado’s legal protections against discrimination, and as a private business owner, Smith had the right to refuse to serve customers based on her religious convictions.

Previously, legal experts say, religious discrimination cases were not common because they traditionally were harder to prove. Now, the Groff and 303 Creative decisions are likely to change that. “We’re entering a whole new world of religion in the workplace,” says Frank Shuster, an Atlanta-based partner at law firm Constangy, Brooks, Smith and Prophete. “It’s a whole new landscape.”

Shuster and other legal experts say the current environment will embolden more employees and advocacy groups to file lawsuits against their employers, especially regarding accommodations that enable them to practice their faith in the workplace.

Legal Ramifications

Recent rulings in favor of religious accommodations for employees have some experts worried about the kinds of accommodations their workers may request. Some requests may create the potential for conflict in the workplace, especially for smaller employers, says Harvey Linder, an Atlanta-based partner at Culhane Meadows. “What might not be a burden for IBM could be for Mary’s flower shop,” he explains.

Lawyers fear dealing with questions such as: What if an employee says their faith requires them to proselytize, and they do so in the workplace? What if an employee refuses to work with a gay colleague because their religion condemns homosexuality? What if a company is accused of favoring one religion over another after accommodating a faith-based request?

Indeed, lawsuits like the one filed last year by Courtney Rogers alleging religious discrimination are becoming increasingly common. Rogers says her former employer, global food service provider Compass Group, fired her after she requested a religious accommodation that would excuse her from involvement in administering a workplace diversity program that she says promised promotions to participants, but excluded white men.

Rogers, who worked in the HR department, argued that her faith prevents her from participating in such an activity, saying, “I believe that nobody should be identified by or restricted by their gender or race, because everybody is created equal under the eyes of God.”

According to court documents. Rogers’ supervisor did not engage in an interactive process regarding her request for a religious accommodation, and he fired her, citing her failure to perform job duties. Rogers, who maintains that her informal reviews had all been positive, filed her suit in July. Compass Group did not respond to requests for comment.

Legal experts say that to avoid disharmony, employers should be transparent about why they may make certain accommodations at the request of specific employees.

Sara Axelbaum, global head of diversity, equity and inclusion at digital marketing firm MiQ, says an employee will occasionally complain about accommodations that the company has made for a colleague for a religious reason. When that happens, Axelbaum explains the reason for the accommodation in the hopes of creating some empathy on the part of the disgruntled employee. She adds that MiQ gives employees two personal days off per year that can be used for any reason, including religious observances. “You are never going to satisfy everyone,” Axelbaum notes.

Respect, empathy and humility are core values espoused by most religions. While some religious beliefs might be offensive to others, those core values aren’t.” —Brian Grim

Conversations about faith can help quell dissent over accommodations, says Brian Grim, founding president of the Religious Freedom & Business Foundation, an Annapolis, Md.-based nonprofit that educates leaders, policymakers and consumers about the positive benefits that faith can have in the workplace.

“Respect, empathy and humility are core values espoused by most religions,” Grim says. “While some religious beliefs might be offensive to others, those core values aren’t. In religious DE&I initiatives, it’s important to define what they are about and what they aren’t. Among other things, they are about information, engagement and celebration; they are not about dogma, proselytizing or the culture wars.”

Employee Resource Groups

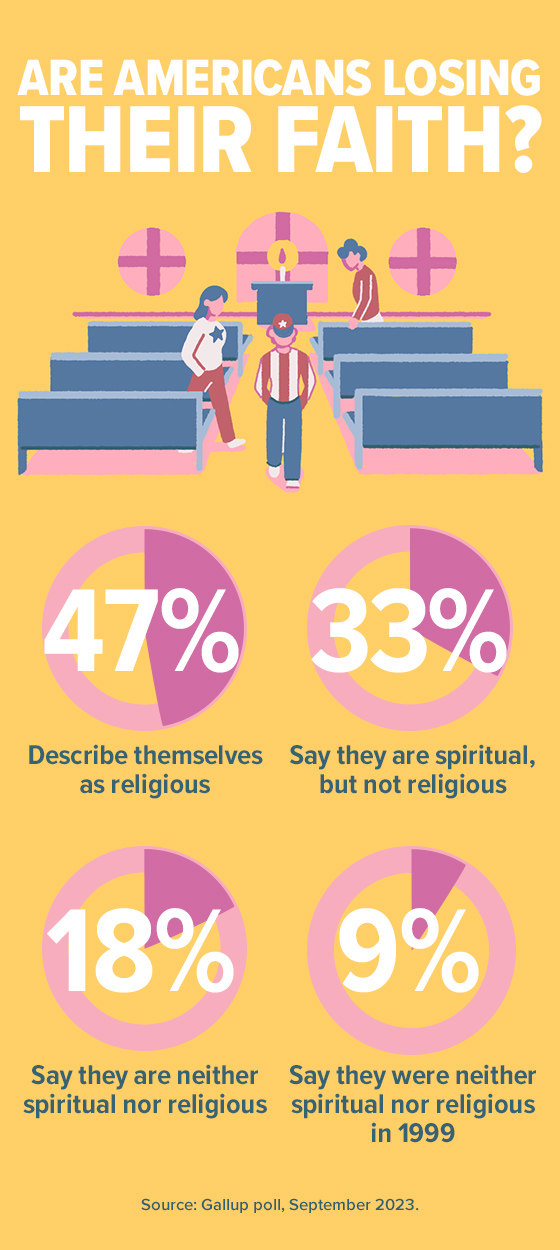

The focus on religion in the workplace is noteworthy considering that organized religion is becoming less important to many Americans. The number of self-reported religious Americans has been on a slow decline. Less than half (47 percent) say they are religious, down from 54 percent in 1999, according to a Gallup poll released in September 2023. About one-third of Americans say they are spiritual but not religious. However, the percentage of Americans who say they are neither religious nor spiritual has jumped to 18 percent from 9 percent over the past 24 years.

Still, many of the faithful desire a voice at their companies. Roughly two years ago, a group of religious U.S. employees at the global software company SAP requested permission to start a faith-based ERG. Jada McFadden, a people experience manager in SAP’s Global Diversity & Inclusion Office, says the employees felt they couldn’t talk about religion at work, and they wanted to end that taboo.

McFadden says SAP gave permission for the group to form, and it has made a major impact during its relatively short tenure. Among its accomplishments are helping to create a guidebook for managers that explains different religions and includes a calendar of holidays. The book is especially focused on non-Christian religions that many employees may not be familiar with. “Instead of employees constantly having to explain themselves, we now have a book,” McFadden says.

There were other successes, too. When SAP began renovating a building in Germany, members of the ERG asked if it could include a prayer room and an adjacent space with running water for Muslims to perform ritual purification, which includes washing their feet. The plan had already included a prayer room, but it was revised to include a purification space as well.

The interfaith ERG at San Francisco-based software company Salesforce has also created materials and training for managers to help them better understand various religious traditions, and it has established spaces for prayer in the workplace. Created in 2017, the ERG, named Faithforce, has also informed some of the company’s products.

Michael Roberts, a solutions engineer and the president of Faithforce, says he has helped tailor products sold to faith-based organizations, such as improving his company’s donation form interface. Recently, the group started working with the Salesforce team tasked with ensuring the company is using AI ethically.

A devout Christian, Roberts says he wasn’t always comfortable talking about his faith. He says a gay friend once remarked that it was easier for the friend to be out about his sexuality at work than it was for Roberts to be openly religious. That remark motivated Roberts to create Faithforce. He says that feeling free to speak about religion affects how people carry themselves at work.

Restricting employees’ conversations about religion “stifles their creativity in the workplace and stifles transparent relationships,” Roberts says. “Bringing your full self to work helps you do your best work.”

Chaplains at Work

ERGs aren’t the only avenue employers can take as they strive to create faith-friendly environments. Springdale, Ark.-based Tyson Foods has employed industrial chaplains since 2000. Each of the 100 chaplains are assigned to a facility where their role is to foster bonds with employees and help them with their personal and professional needs. That can mean lending an ear or referring them to other services. Conversations are kept confidential.

At the end of each month, without using any identifying details, the chaplain discusses employee concerns with the facility’s management and HR representatives. Tyson views the information as a tool to help create a better work environment for employees. The chaplains “allow people to really show up and say who they really are and say what they really think and say what they really feel in a psychologically safe environment,” says Kevin Scherer, director of chaplain services in Tyson’s HR department.

Chaplains do not discuss religion with employees unless employees bring it up, although chaplains are sometimes involved in addressing faith-related issues. For example, Carrie Kreps Wegenast, a chaplain supervisor at a Tyson facility in New London, Wis., says she arranges for Muslim employees to take breaks in conference rooms while fasting during the month of Ramadan so they aren’t near colleagues who are eating. Kreps Wegenast says that since she knows the faith of most of the 700 employees at the facility, she often asks about workers’ holiday plans, creating another touch point for her to interact with employees.

Chaplains can also help when confusion arises over employees’ religious practices. When Kreps Wegenast worked at a plant in Green Bay, Wis., several years ago, a group of Muslim Somali refugees was hired at the facility. The new employees didn’t communicate to managers that they needed to pray periodically, leaving colleagues and managers baffled when they abruptly left the production line, often letting food go to waste. Kreps Wegenast reached out to a local imam for help developing accommodations that would allow Muslim workers to pray in a designated place without interfering with food production.

The experience led Kreps Wegenast to talk to employees about their faith and share what she learned with all employees to promote better understanding of one another. Before her efforts, Kreps Wegenast says, employees interacted only with members of their own ethnic or religious group during breaks. Eventually, however, she saw them sitting together and laughing with one another.

“I felt like there was a sense of community,” she notes.

Theresa Agovino is the workplace editor for SHRM.

|

Many of today’s expressions of religious faith—and sometimes intolerance—occur on social media, and often on work apps such as Slack and Teams. Workplace experts say employers should ensure they have and make widely available a carefully constructed social media policy that provides clear instruction on what behavior and speech are and are not acceptable at work. “There has to be some sort of clear, rational, explainable guideline that employees can reference,” says Edward Ahmed Mitchell, national deputy executive director of the Council on American-Islamic Relations, a Muslim advocacy group. “You can’t just have a free-for-all of people accusing each other of being offensive and getting fired.” In addition to spelling out the rules for employees regarding respectful communications, company leaders can adopt practices that, while not addressing specific religious faiths, do enable their employees to practice their religion without impinging on the rights of others. Some ways employers can do this include:

|