Employers Say Students Aren't Learning Soft Skills in College

Part 2: College grads are deficient in critical thinking, teamwork, speaking and writing, executives say

Part 1

Promise of a 4-Year College Degree

Part 2

Students Aren't Learning Soft Skills

Part 3

College Grads Lack Hard Skills, Too

Jim Link's college-age son came home this summer with a problem: Assigned to clean up a database at his internship, he first had to confirm that the data were accurate and up-to-date.

But the people who could help him didn't reply to his e-mails, responded too slowly, failed to show up for meetings or weren't up to speed on the data.

For a week, Link coached his son through this challenge.

"I taught him about being inspirationally irritating," said Link, CHRO of Randstad North America, a leading staffing company, in Atlanta. "It means saying what you need persuasively, up to the point of driving people nuts. What I was really teaching him was how to work with other people—about influence, negotiation and persuasion."

His son's experience, Link says, illustrates the lack of creative problem-solving that he sees in today's college students.

How Important Are Soft Skills?

What Link describes are what today's business world calls "soft skills." And the classic four-year college education, with its emphasis on critical thinking, debating, viewing issues from several angles and communicating clearly, was designed to teach these skills.

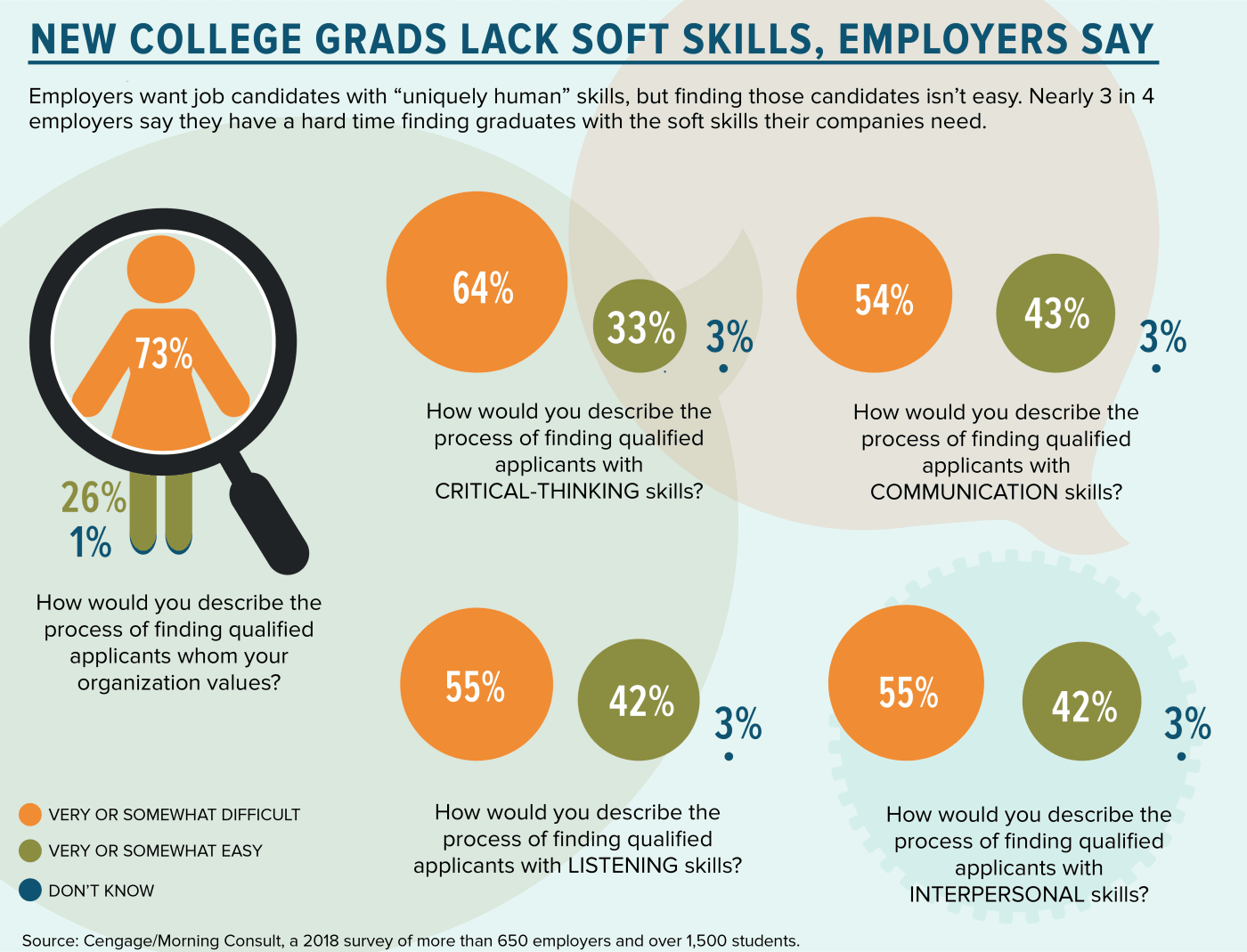

Yet nearly 3 in 4 employers say they have a hard time finding graduates with the soft skills their companies need.

In a 2019 report, the Society for Human Resource Management found that 51 percent of its members who responded to a survey said that education systems have done little or nothing to help address the skills shortage. The top missing soft skills, according to these members: problem solving, critical thinking, innovation and creativity; the ability to deal with complexity and ambiguity; and communication.

Are college curricula just different than in years past? Are college students different? Has a reliance on technology robbed young adults of soft skills? Or have today's companies—many of them startups and dependent on ever-changing technology—grown impatient and unwilling to wait out what was once a predictable, on-the-job learning curve?

All of those questions may hold the answers, say the executives, educators, students and workplace experts interviewed for this series.

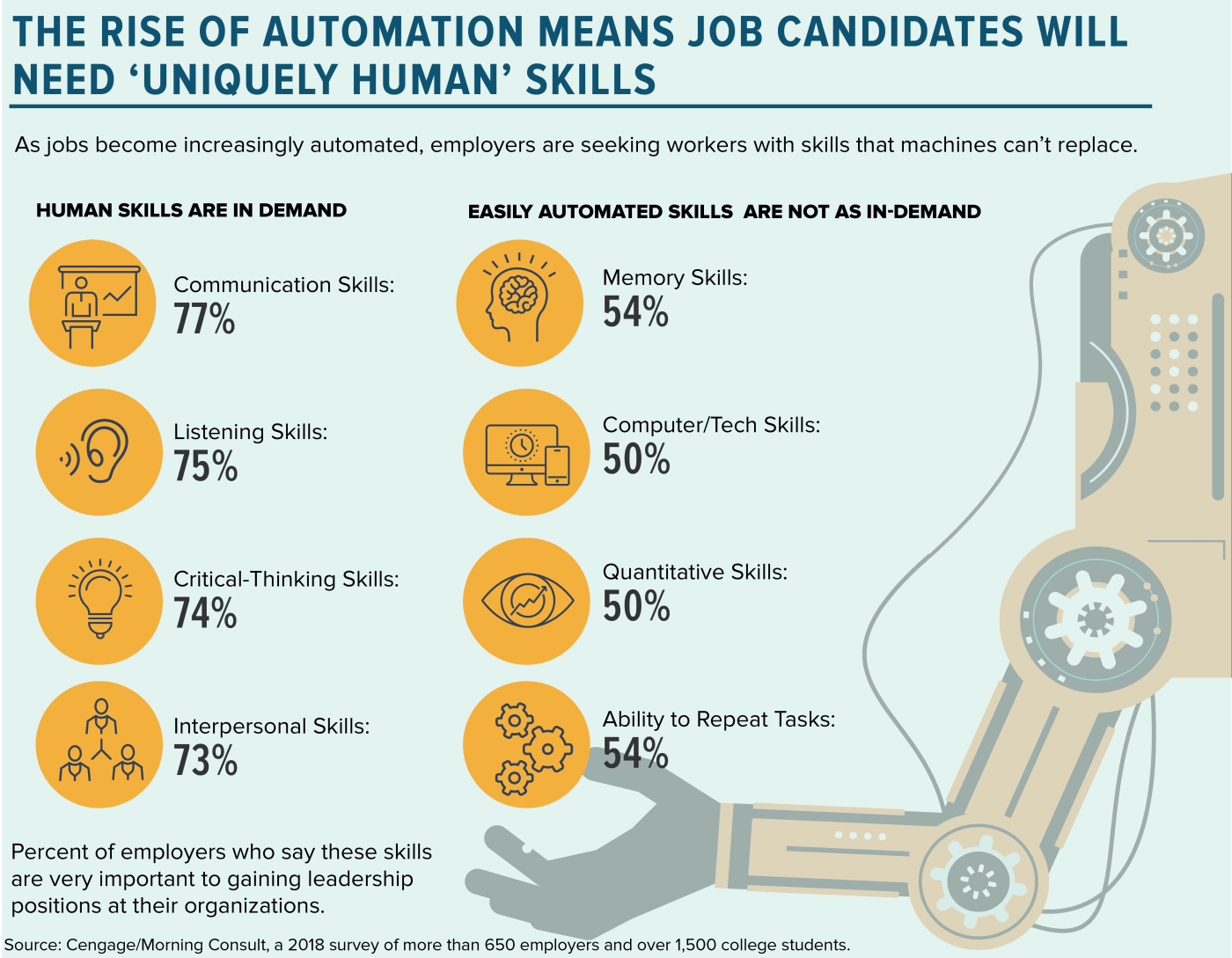

In the immediate future, the most valuable work skills will be those that machines can't yet perform, like soft skills, according to a survey by the Pew Research Center of about 1,400 technology and education professionals. The survey suggested that young adults need to "learn how to learn" if they hope to adapt to a fast-changing work world.

Link likes to think further ahead—to 2025, when many familiar jobs will be performed by machines. Machines will be doing basic tasks that require abilities such as operational skills (functioning as forklift operators, assembly line workers), administrative skills (secretaries, bank tellers) and computational skills (accountants).

Soft skills are precisely the skills that a traditional four-year college degree, especially in the liberal arts, is designed to teach, said Lynn Pasquerella, president of the Association of American Colleges & Universities in Washington, D.C.

"I was a philosophy major," Pasquerella said. "We composed arguments about issues, responded to objections, developed a capacity to imagine what it's like to be in the shoes of someone different, to listen critically and to consider points of view that might call into question your fundamental beliefs."

Year after year, her organization's annual survey on the skills that company executives consider most valuable in college graduates and that prepare students for the workforce finds that soft skills "are the best preparation for long-term career goals."

Yet "these are areas where colleges are clearly struggling to prepare students," said Denise Leaser, SHRM-SCP, who is president of GreatBizTools, an HR management products and consulting services company in St. Paul, Minn., and whose daughter just graduated from California's Biola University. "And the future appears to be worse."

Chris Kirksey is president of McLean, Va.-based Direction.com, a digital marketing and Web design company. He said he's interviewed "many brilliant people with college degrees," some of them with multiple degrees. But he often finds them wanting.

"It seems college is graduating many 'book-smart' people with no real people skills or no real-world use of their knowledge skills," Kirksey said. "What's so great about a degree in something if you only know about it, and not how to teach it, use it, or understand why people want or need it?"

What's Happening at College?

Pressured by businesses to produce graduates with up-to-date technical skills, colleges could be relaxing their standards for requiring liberal arts classes—precisely the types of classes that research has shown develop the soft skills businesses also want.

"A lot of colleges still have curricula grounded in the liberal arts," said Martin Van Der Werf, associate director for editorial and postsecondary policy at Georgetown University's Center on Education and the Workforce. "But most could also be accused of chasing after what they think most businesses want ... what the next hot major is. And designing curricula to bring students up to snuff on the technical skills they need for a degree sometimes comes at the expense of grounding them in the liberal arts."

For example, he said, a college business degree can now be splintered into several subdisciplines (such as a specialty in supply-chain management), each requiring its own specific expertise. "So the emphasis becomes trying to [introduce] new classes, so they'll shave off one or two of the core liberal arts requirements."

In addition, he said, colleges are more consumer-oriented today. Because the public can track from year to year what new college graduates earn, schools feel pressure to demonstrate that college tuition is worth the investment, especially at a time when tuition costs are through the roof.

"For colleges, it used to be 'Hey, we're a place where students can come and find themselves, learn about their passion and follow it,' " Van Der Werf said. "As the tuition sticker price rose, the leverage has switched to consumers who say, 'I invest thousands in my education. What guarantee can you give me that I'll get a job when I'm out, and how much will I make?' More and more, colleges are listening and saying, 'OK, maybe it's not the wisest thing to require political science for a business major.' "

Zachary Schallenberger is a rising senior at Montana State University in Bozeman, majoring in computer science. Like most of the computer-science students interviewed for this series, he confessed that college hasn't really taught him some basic interpersonal skills, which is important for science-inclined students who can be introverted and socially awkward.

It wasn't at the university but at an internship at BMW where he first learned these skills.

"One of the things I quickly had to learn was to communicate in a professional environment," he said. "That was never taught to me. What's the formal way to write an e-mail? Is e-mail the most appropriate way to contact someone? How do I have conversations with my manager?"

Is Digitization to Blame?

Eric Frazer has another explanation for the dearth of college graduates with soft skills—and it has nothing to do with college curricula.

College students are more disengaged than students of decades past from campus sports, Greek life, volunteerism and other extracurricular activities that grow soft skills.

"Students are not getting as involved in the opportunities that could develop these skills," said Frazer, who teaches part time at Yale School of Medicine. "Before, one would join a fraternity or sorority, a recreational club, a sport, theater, music—where there's a hierarchy, leaders, where you learn interpersonal and conflict-resolution skills.

"Now [students'] social connections are online. Instead of joining a club, people join an app or an online group. Instead of sitting down with someone and sharing, they share photos and news snippets on phones and tablets."

Link agrees.

"I see this even in my own household," he said. "I am raising four Generation Z students. "While they completely recognize that they need to be persuasive or to manage conflict, they're often perplexed as to how to make those things happen. I think it's because they've been 'digitalized' at a very early age and taught to believe that the best way to solve a problem is go to a machine and find your solution, instead of to another person."

Part 3: Students' hard-skills gap.